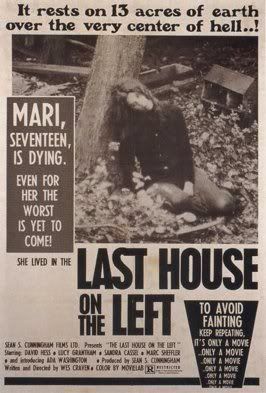

The film's biggest draw, though, has always been the central story: scumbags rape and murder innocent girls, and then unfortunately (without knowing the truth) seek refuge in the home of one of their hours-earlier victims, which the parents figure out and wage unholy vengeance. It's such a basic, everyday nightmare setup, one of those "how would I react if that were my loved on?" scenarios that can be interpreted in so many ways, and when in the hands of a deviant filmmaker such as early Craven can bless the pupils with oodles of gore and anarchy. The love of a family member called into immediate, extreme, retaliatory action.

[WARNING: THIS CLIP IS SPOILER-CENTRAL, IF YOU'VE NEVER SEEN LAST HOUSE AND WANNA SEE IT SOME DAY IN FULL CONTEXT WITH SURPRISES]

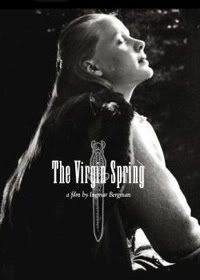

The lesser-informed moviegoer may think that this crackerjack of a revenge-tale idea belongs to Craven and his associates back in the '70s, but such an un-studied chap would be dead wrong. The truth is, the Craven crew directly lifted the story from an age-old fable called "The Virgin Spring," a classic that was brought to cinema by iconic Swedish director Ingmar Bergman back in 1959. Bergman's films are known for their slow-to-numbing-degrees pacing and beautifully haunting imagery, and The Virgin Spring is considered by many to be his best.

Rather than have to toss the flick into my now-300-DVDs-deep Netflix Queue, I was able to DVR it thanks to the wonderful IFC Channel's slept-on (pun intended, duhhh!) after-hours programming. It's a relatively quick film (only 90 minutes), but Bergman takes his time so painstakingly that the film feels like a marathon. Not in a bad way, however; even considering that I pretty much knew what was going to happen here (having seen Last House on the Left numerous times), I was still held captive from jumpoff to landing. Several lasting images are sprinkled all about, and cerebral religious themes are tossed in. In other words, Bergman's The Virgin Spring is the polar opposite of Craven's Last House ---Craven scrapped any underlying message and went strictly for crimson-covered shock value. His is like the grindhouse version of what Bergman accomplished some nearly-20 years earlier.

Which do I prefer? I hate to say it, since I realize how it's a level of cinephile blasphemy, but I'm more for Craven's take. I can admit why, however, with a straight face: I'm a guy who loves line-crossing exploitation and visceral things. The Virgin Spring is an exemplary, magnificent flick, there's no doubt...but it's almost too subdued for my tastes. This is coming from a guy who considers slow-burners such as 2007's There Will Be Blood and even the impressionist, Germany-issued 1920s' Vampyr to be masterpieces, so how's that for hypocritical, contradictory, eh?

The nuts-and-bolts of the story is the same here as Last House, the biggest differences being: rather than going on an unchaperoned concert trip with her sassy friend, the daughter here (named Karin) heads off to a church to deliver candles (The Virgin Spring takes place in 14th century Sweden, so mostly all plot-points serve its time-frame), and she's the only girl raped and murdered by the bastard strangers, who are three inbred-looking brothers/herdsman that Karin, in all her naive gullibility, sits down with for a picnic. The central rape/murder setpiece is a much quitier beast here, too. Bergman keeps it sans music, using facial close-ups and impeccable lighting tactics to drive home the "loss of innocence, and then loss of breathing life" impact like a gavel. In terms of sheer chills, Bergman's handling of this moment is far more effective than Craven's. The exposed-entrails and off-kilter, murky musical cues Craven punctuates his take with give the whole thing a much dirtier, why-am-I-watching-this feel; Bergman, on the other hand, hypnotizes you, smacking your sympathetic side more. By the time Karin was lying dead and disrobed in the forest, snow falling down on her as she's left to rot, you're sort of paralyzed with remorse and rage. Why did she have to die such a cruel death? She was just a smiling, kind, all-too-gullible little gal? At least that's what I thought.

It's probably because I'm not the most religion-minded cat around, but the obvious God-fearing themes here didn't hit me as hard as I'd imagine Bergman intended for. Karin's father, Tore, is a devout Catholic, as is her loving mother (who dresses oddly similar to the Virgin Mary my Catholic school textbooks illustrated), and when he finds out that the three herdsman sleeping under his roof killed his virgin daughter earlier, his boiled-over rage prompts him to slice-and-dice, without consulting a God who he feels has forsaken him. But after he's dispatched of the bad guys (one being an innocent little boy who didn't do anything to Karin, whose on-screen death makes me think that The Virgin Spring raised many an eyebrow back in '59/'60), Tore still prays for God's forgiveness. The whole notion of "does God really watch over us no matter when the time, even when a loved one is killed for no good reason?" is laid out clear as crystal. But again, I was more effected by the unjustified, premature death of a little girl and the vengeful repercussions than any Sunday School BS. Heathen, much?

The amount of memorable shots seen in The Virgin Spring far outweighs those of Last House on the Left, it should be said. Watching, through the in-focus flames of a fire, the father jam his dagger into the heart of one of the villains; the opening close-up of Ingeri's, Karin's jealous travel companion who watches her demise without helping, striking face (piercing eyes, and long rectangular lips) that is creepy-city; and the last staggering, disbelieving moments of Karin's life, right up to her lifeless, just-beaten-in-with-a-thick-branch, bloodied head trying to lift itself up for one last breath, and failing.

Bergman could shoot the ever-living shit out of a scene; the otherworldly, visually tangible-nightmares he delivered in the eerie-as-a-mug Hour of the Wolf (the only other Bergman joint I've seen, which I hope to change soon) alone have proven his legend to moi.

In closing (cringes in self-film-lover-loathing)....

Craven's Last House on the Left > Bergman's The Virgin Spring

Hey, it's a personal preference matter. Get over it.

No comments:

Post a Comment